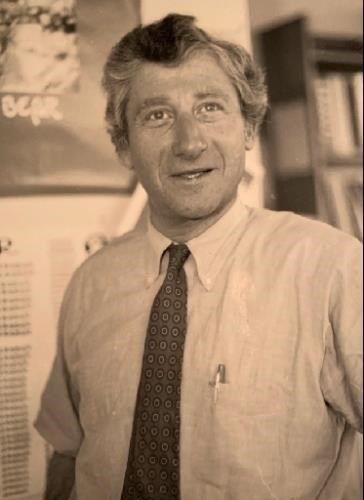

Saul Zaik

The Architect Who Refused to be Forgotten

by Brian Enright

Saul Zaik spent more than six decades proving that Northwest modern architecture wasn't just about following what Belluschi and Yeon had pioneered. There was room for more, and he took their ideas and put his own unique stamp on them to make his own style. While some of those earlier masters moved on to bigger buildings and academic appointments, Zaik stayed focused on designing houses that helped people understand how they wanted to live. It was his professional passion.

Zaik worried, sometimes, about being what he called "the forgotten man" because he was the architect who came after the famous pioneers, and he never really achieved their household-name status. But he worried in vain, because he defined what Northwest Regional Modernism meant for an entire generation, designing homes so distinctive that people still refer to "Zaik houses" the way they might reference Eichlers in California.

From Navy Radio Operator to Architect

Zaik's path to architecture started with drawing, a skill that served him well when he graduated from Portland's Benson Polytechnic and joined the Navy during World War II as a radio operator on a Pacific transport ship. After the war, the GI Bill sent him to the University of Oregon, where he earned his architecture degree in 1952.

His early career moved quickly. After working at several small firms, he landed at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill's Portland office at age 28. This was a significant moment as SOM Portland had recently been Pietro Belluschi's office before being acquired by the legendary national firm, and was about to produce two Oregon landmarks: Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Portland and The University of Oregon's Autzen Stadium in Eugene.

But Zaik's time at SOM was cut short by what might be one of the most romantic gestures ever in the history of architecture. He was set to marry Frances Lowry in 1955, but his boss at SOM suggested his job might be at risk if he took a honeymoon. Zaik made his choice and left to start his own practice, choosing marriage and independence over job security.

Defining a Regional Style

By 1973, a profile in Symposia magazine captured what Zaik had become: "When one thinks of Oregon architecture one immediately envisions weathered wood structures resembling Willamette Valley farm buildings. The Oregon architect of the current generation most sympathetic and skilled with this vernacular is Saul Zaik of Portland."

This wasn't accidental. Zaik deliberately developed an approach that honored both international modernism and Oregon's agricultural building traditions. His homes featured asymmetrical floor plans, flat or low-pitched rooflines, extensive use of hemlock and fir, and complex forms that somehow remained simple.

What made Zaik's work identifiable was his ability to integrate the building with its landscape, bring the outdoors inside, use natural materials and prioritize how people actually live and use the space over architectural theory. Whether designing for steep forested hillsides or the Oregon coast, Zaik looked for ways to dissolve the boundary between dwelling and nature.

The Feldman House and Beyond

One of Zaik's best-known designs, the 1956 Feldman House, tells a story about both his architectural approach and his social consciousness. Built for a Jewish couple who had emigrated from Germany after the war, the house had a budget of just $35,000 (about $338,000 today). Rather than see this as a limitation, Zaik created what many consider a quintessential example of Northwest Regional Modernism.

The house featured towering bathroom ceilings, dramatic floor-to-ceiling windows in the living spaces, exposed beams, and extensive use of hemlock and fir. He chose those materials because they were affordable while still echoing the Willamette Valley landscape that Zaik admired.

His own residence, completed in 1961 on a forested hillside near Forest Park, demonstrated his ideas in pure form. Divided into two pavilions connected by glass-walled entry spaces and cantilevered decks, the house sits among Douglas firs and maples that come within inches of the facade at points. Living there for nearly six decades, Zaik practiced what he preached about connecting with the outdoors and living modestly but well.

A Long Career and Even Longer Legacy

Zaik practiced architecture actively from 1956 until his death in 2020 at age 93. A year before his death he recorded an interview with the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education that I'd highly recommend reading or listening to.

Zaik's work can be found throughout Oregon. He built houses, condominiums and apartments, and each is identifiable by those simple rooflines, complex forms, natural materials, and seamless integration with landscape. His LongHouse Condominiums on the Oregon coast, his various Portland homes scattered through the West Hills and even his experimental designs like the one-bedroom atop a 65-foot-tall World War II ship demonstrate how Zaik never stopped exploring how modern design could serve Northwest living.

Saul Zaik didn't become the forgotten man. Instead, he became the architect whose work defined what Northwest Regional Modernism meant for generations of Portlanders who wanted homes that honored both modern design principles and Oregon's distinctive landscape. Every time someone describes a house as having that "Northwest modern feel," they're probably thinking of qualities Saul Zaik spent six decades helping to perfect.