William Fletcher

Mies + Portland = Fletcher

by Brian Enright

Unlike most recent graduates, William "Bill" Fletcher graduated from architecture school at the University of Oregon with a clear vision. He wanted to bring the rigorous geometry of International Style modernism to our forested hillsides here in Portland. Over the next five decades, he proved that Mies van der Rohe's glass-and-steel aesthetic could absolutely complement the emerging Northwest Contemporary aesthetic.

He loved the clean lines, the transparent planes, the honest expression of structure in European modernism. But as a lifelong Portlander he also understood that Oregon wasn't Illinois, and our misty forests demanded something different than Chicago's urban grid. His homes became iconic examples of international modernism that felt unmistakably rooted in the Pacific Northwest.

Rooted in Portland

Like John Yeon, Bill Fletcher came from a prominent Portland family. His great-grandfather, Morris Fechheimer, was a prominent local attorney who commissioned the landmark Fechheimer & White Building on Naito Parkway. The building, which is still standing today, is regarded as one of Portland's finest works of cast-iron architecture.

Fletcher's father, William Blackstone Fletcher (1875-1948), was also a successful businessman who owned considerable real estate in Portland. He owned the land along the Willamette River south of the current Sellwood Bridge which is now

Powers Marine Park. His father changed the family name from Fechheimer to Fletcher amid all the growing anti-German sentiment after World War I.

From a Basement to 14th Street Office

Fresh out of architecture school in 1950, Fletcher took a brief detour into cemetery design, working on mausoleums including one at River View Cemetery. Coincidentally, River View is the cemetery where his grandfather is buried. According to an interview with his business partner Dale Farr, Fletcher's work even caught the attention of Count Basie's family, leading to a commission for the jazz legend's final resting place outside New York City. This made Fletcher very happy as he was a musician himself who played drums.

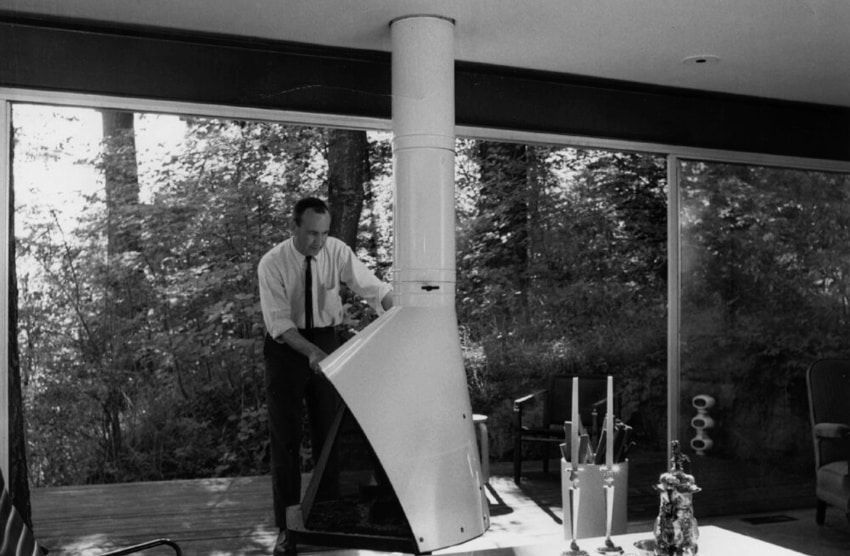

By the early 1950s, Fletcher was ready to launch his own practice. He started modestly, working from his basement while designing and building his own home in Dunthorpe on nearly two forested acres. This first house became both his calling card and his statement of intent: 2,300 square feet of glass, wood, and precisely calibrated views that made the surrounding forest feel like an extension of the living space.

The Portland press took notice. One reporter observed that an architect designing their own home sets an exceptionally high bar - it's both laboratory and advertisement, with nowhere to hide shortcomings. Fletcher's house passed this test brilliantly, attracting clients and establishing his reputation.

By 1956, Fletcher had formalized his practice and moved into professional office space at SW 14th and Columbia. This building housed an informal collective of talented young architects who would become known as the "14th Street Gang" - Saul Zaik, Donald Blair, John Reese, Frank Blachly, Alex Pierce, and designer George Schwarz. They maintained separate practices but shared space, ideas, and occasionally collaborated on projects.

Fletcher formed partnerships with several colleagues over the years. One early collaboration paired him with Curt Finch, a fellow University of Oregon graduate. Their partnership had a musical foundation - Fletcher on drums, Finch on trumpet - and both kept instruments in their car trunks for impromptu jam sessions. Fletcher remained deeply involved in Portland's jazz scene throughout his life, playing bebop gigs at local clubs in the late 1940s and maintaining that passion for rhythm and improvisation that seemed to inform his architectural sensibility.

A Distinctive Northwest Modernism

As I mentioned before, what made Fletcher's work unique was how he adapted International Style principles to Oregon's climate and terrain. He studied Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, an iconic glass pavilion floating in an Illinois meadow, but understood that simply replicating it in Portland wouldn't work.

Oregon's diffused light called for different window strategies than the harsh midwestern sun did. Although these days you'd be hard pressed to notice the difference on some of our recent summer days. But our region's overall temperate climate and abundant evergreen forests created natural privacy screens. The sloping wooded sites Fletcher often worked with demanded careful placement and orientation rather than the flat open meadows that suited Mies's abstract pavilions.

Fletcher's colleagues noted that his architecture possessed an inherent sense of rhythm, likely influenced by his lifelong involvement with jazz. You can see it in the syncopation of vertical posts against horizontal roof planes, in the careful proportioning of solid walls to glass expanses, in the way interior spaces flow and compress and open again. These were jazz-like architectural compositions, carefully orchestrated to create specific and unexpected experiences as you moved through space.

Five Decades of Architecture and Counting

Fletcher's firm still exists today as FFA Architecture and Interiors and has accumulated more than fifty design awards. Architecture wasn't something he retired from or ever grew tired of, and Bill remained actively involved in projects until the day before his death in 1998. He also served on the Oregon Arts Commission, extending his influence beyond individual buildings to shape cultural policy. Former partners and colleagues remembered Fletcher as someone who lived and breathed architecture, and who approached each project with the same intensity whether it was his fiftieth house or his first.

Today, Fletcher's homes are studied and treasured by mid-century modern enthusiasts who recognize his unique contribution to Northwest modernism. He helped define a regional style that honored international modernist principles while being unmistakably of these forests, this light, this climate and this landscape.

His work demonstrates that responding to context doesn't mean abandoning modernist ideals, and that modernist clarity doesn't require ignoring where you are. Fletcher found the geometric order within Oregon's forests rather than imposing geometry upon them. His glass walls didn't fight the surrounding trees; rather they framed them, celebrated them and brought them into the experience of living in the house. Those are the core tenets of Northwest Modernism.